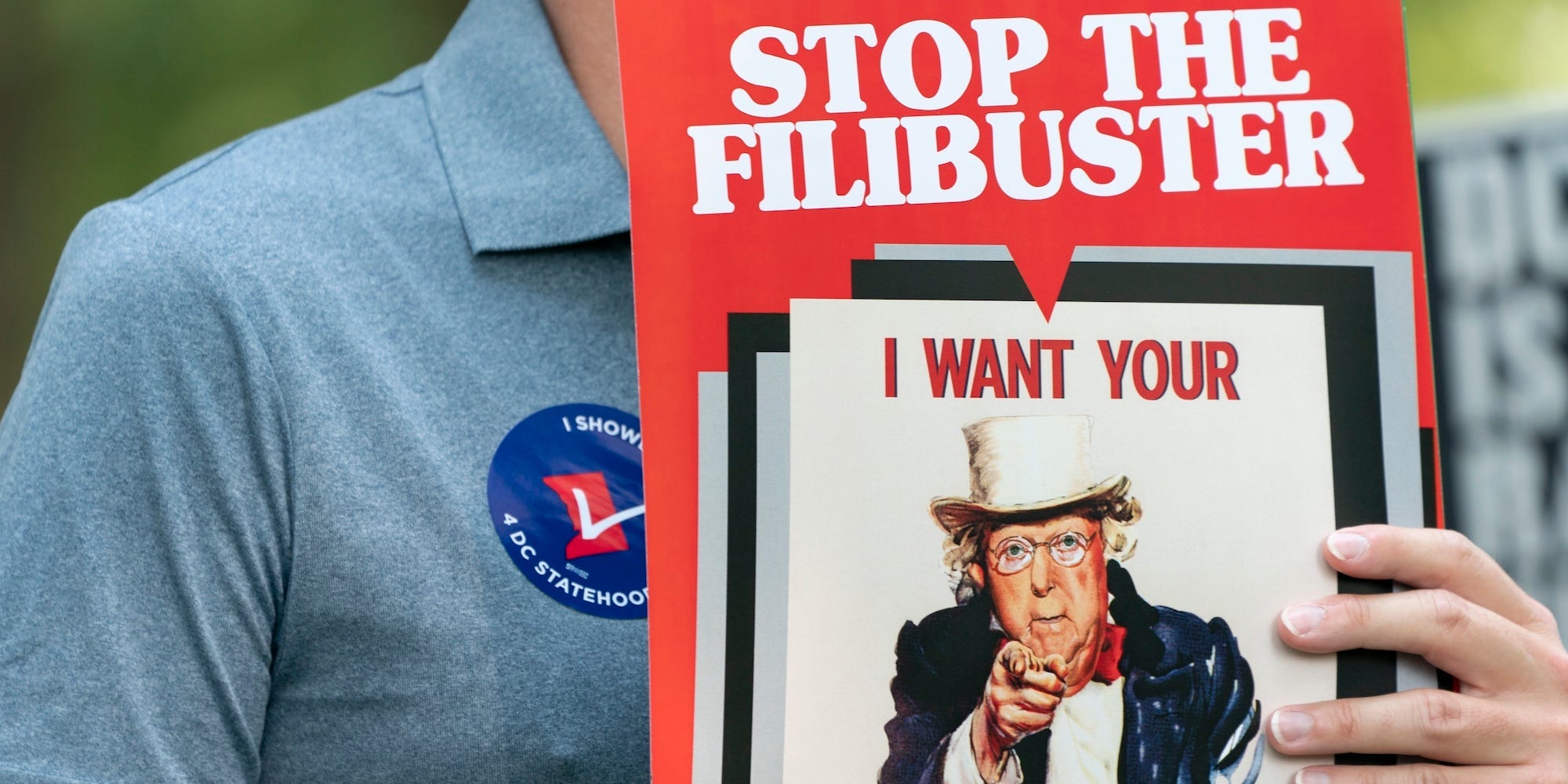

AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin

- Senate Democrats want to make Election Day a holiday, allow same-day voter registration and crack down on gerrymandering.

- But the future of these proposals, in a Manchin-approved compromise bill, aren't looking promising.

- The two parties are largely speaking different languages, with major consequences going forward.

- See more stories on Insider's business page.

Senate Democrats find themselves barreling towards another impasse with their Republican colleagues, with early signs they're getting little to no bipartisan support for election security protections and expanded voting access that some nonpartisan experts say are essential after the disputed 2020 election results.

After Senate Republicans filibustered the For The People Act, Democrats' ambitious voting rights, campaign finance, and ethics package, a group of eight Senate Democrats including key moderate Sen. Joe Manchin went back to the drawing board.

The group unveiled the Manchin-approved compromise bill, The Freedom to Vote Act, on September 14. It throws a bone to Republicans in imposing a nationwide voter identification requirement, but would still drastically reshape the US' election law and campaign finance landscape.

"It's a very bold bill," Steve Spaulding, senior counsel for Public Policy & Government Affairs at Common Cause, told Insider. "It is still a sweeping, bold bill with many of the main pillars of the For The People Act in it."

The legislation would make Election Day a holiday, require states to adopt automatic, same-day, and online voter registration, require early and no-excuse mail voting in federal elections, restore voting rights for formerly incarcerated people, and crack down on partisan gerrymandering in redistricting.

It also includes new protections for the safety of election workers and the integrity of election materials and results, both of which have come under attack in 2020 and in the last election's aftermath.

But the bill is likely to suffer the same fate as the For The People Act under the Senate's current rules, which require most legislation to reach a three-fifths majority.

Despite Manchin's core philosophical insistence to get Republicans on board, the Freedom to Vote Act doesn't appear to have a chance of getting any more GOP support than its predecessor, with Minority Leader Mitch McConnell flatly saying "we will not be supporting it."

Sen. Susan Collins of Maine, a GOP Manchin ally, said she supported provisions in the bill cracking down on "dark money" in elections and requiring campaigns to report foreign interference to the FBI, but raised concerns about the bill constituting a federal overreach.

"The fundamental problem of federalizing state elections appears to remain in the bill," she told reporters at the Capitol. "I represent a state with one of the highest turnouts in the country, consistently, and I do not see why they should have to jettison their system and adopt a new federally mandated system when our voting laws work very well."

And a spokesperson for Sen. Lisa Murkowski, another top GOP Manchin ally, told NBC News the Alaska senator "is concerned that it has some of the same flaws as For the People Act-overreach by the federal government into states' election systems."

AP Photo/Andrew Harnik

Other Republicans who have proposed similar policies appeared unlikely to support Manchin's plan. Sen. Rick Scott of Florida, a Republican, introduced two bills in in late 2020 and early 2021 that would require voter ID nationwide, ban automatic voter registration, prohibit states from sending ballots to all registered voters, and set uniform standards governing how states administer, process, and report absentee ballots.

But in a brief interview with Insider at the Capitol, Scott said: "Elections should be run by our states."

"The states are doing their job. The states are trying to constantly improve their election laws - I did it for eight years as governor. We shouldn't be taking over federal elections," he added.

When asked about how that view of Congress' role comports with the bills he's proposed, Scott said, "I think we should require that you have to show your ID to vote."

Spaulding argued that the bill wouldn't usurp the state's authority to devise their own rules, but set more uniform standards and a "bare minimum floor."

"While we're electing one president and one Congress, there are 50 different state election codes that govern our federal elections," he said. "And that just leads to a really unfair set and confusing set of rules."

'Extreme partisanship'

After the 2000 election debacle, both parties agreed the US election system was in crisis and needed some major overhauls. After months of painstaking back-and-forth negotiations, leaders of the two parties finally reached a bipartisan compromise bill, The Help America Vote Act, in October 2002.

But this time, members of both parties are occupying largely different universes. Republicans in state legislatures around the country are using their majorities to pass new voting and election laws that Democrats and many nonpartisan groups criticize as unnecessary at best and repressive at worst - and Republicans in Congress are in no rush to stop.

"What we've seen in Texas is extreme partisanship, and it is because of gerrymandering that translates into elected officials only caring about primary voters, the most extreme partisan in the electorate," Democratic Texas State Rep. Gina Hinojosa, one of the members who left the state over the summer to try and block the passage of election legislation, told Insider.

In a recent Election Law Blog post, Ohio State University Law Professor Ned Foley suggested that Democrats should sit down with Rep. Liz Cheney, the most vocally Trump-critical Republican House member, and devise legislation "for protecting America's representative democracy from an authoritarian takeover."

But because of how Republican primary voters call the shots, the greatest challenge to a bipartisan approach may be getting members of Cheney's own party, not Democrats, on board.

A fellow member of the three-person Wyoming congressional delegation, Sen. Cynthia Lummis, cut off a reporter who asked about one of Cheney's primary challengers, and said, "You know what, I'm not talking about Liz Cheney anymore."

Jacquelyn Martin/AP

The latest voting rights bill also captures intraparty philosophical debates about the filibuster, which a growing chorus of lawmakers and activists have called to be amended or scrapped altogether to pass democracy protection legislation.

"We have, as you know, Senator Manchin, who believes that we should try to make this bipartisan," Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer said at his September 14 weekly news conference. "If that doesn't happen, we'll cross that bridge when we come into it. As I've said, all options are on the table."

But Manchin and Sen. Krysten Sinema of Arizona have said they oppose amending the filibuster to pass civil rights legislation with a simple majority, both warning of the consequences that could ensue when Republicans retake the Senate majority.

In the eyes of many advocates, it could be too late by that point to shore up American democracy.

"I think there is room for common ground, but at the end of the day, given that we're talking about the fundamental freedom to vote, we need to give Senator Manchin room to bring along the Republicans that will see the wisdom of supporting this revised bill," Spaulding said. "But at the end of the day, if that doesn't happen, we do think it's incumbent upon the majority to find a path forward to get this bill to the president's desk."